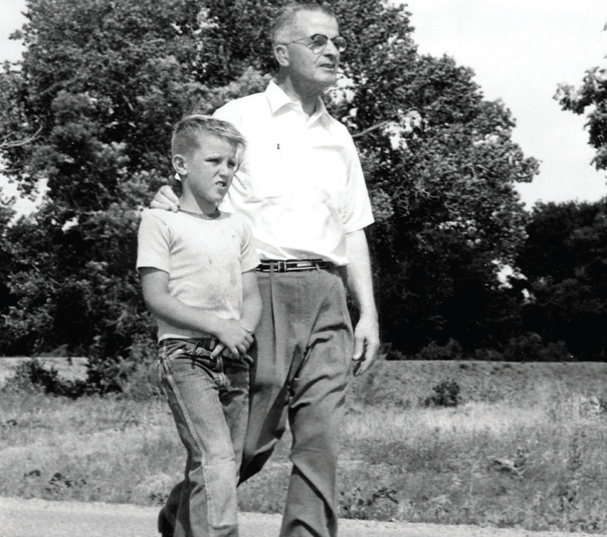

Earl spent his first seven years in a children’s home before he arrived at Cal Farley’s Boys Ranch in 1957. One sunny day when he was nine years old, he was playing in the plum patch at Boys Ranch and standing in the creek water. “I heard a man yell at me to get out of the water, but I ignored him and I disobeyed. Next thing I knew, he reached over and grabbed me by the ear. It was Cal Farley. He told me, ‘Let’s go for a walk.’”

Sherm Harriman had been out taking pictures for most of the day and only had one more picture left on his film. That last picture ended up becoming the iconic “Shirttail to Hang Onto” photograph the Cal Farley’s organization has used for several decades. Earl Jordan didn’t think nearly as much of it. “You’ve got to realize that at 9 years old living at Boys Ranch and that picture being plastered on the dining room wall … the nickname that stuck was ‘mooch.’”

Earl left Boys Ranch in 1965. Shortly thereafter, he met Carol on a blind date, and on that very first date, he proposed. They have been married for 44 years.

“She was God-sent,” he said. “I had nothing before her and now I have the world.”

The couple, over the years, has striven to take care of children much like Cal Farley, Earl explained. As such, he and his wife have worked as house parents, teachers, and mentors and have helped to care for close to 100 children in Arkansas and in Arizona. “When you have walked in their shoes you can understand where they come from … and you know how to distinguish ‘the hates,’ ‘the hurts’ and ‘the chips.’ We tried to treat them as Cal Farley treated all us boys — once a kid came in, we were his.” The North Phoenix resident has spent his life paying it forward. “We had gardens for a while,”

he mentioned. What he meant by “gardens” were community produce gardens that he would seek permission from land owners to grow fresh fruits and vegetables. All the produce from these gardens then was delivered to the elderly in the area. He also held food drives in car lots. “I just tried to do a little bit of what Cal did and I wouldn’t make a hair on Cal’s head,” he said, humbly. Another way he mimicked Mr. Farley was by seeing to it the boys in his low income neighborhood were given the opportunity to play baseball. He formed a team each season, and if a boy wanted to play, he earned the privilege to play on the team by picking up trash in the area on Saturdays. Earl would raise the money, from local businesses, to pay the fees and buy the uniforms for the children to play. “My kids were poor just like me. Every Saturday we cleaned and it was their team.” His recent visit to Cal Farley’s Boys Ranch helped him to realize the breadth and depth of what Cal Farley’s does for the youth they serve today. “Cal Farley’s gets the kids ready for life, and then they support them afterwards,” he pointed out. “It became the greatest thing in the world that ever happened to me.” He explained that as a child he suffered from severe dyslexia and never did well in school. “But Cal Farley was all around. He knew when a boy couldn’t learn and needed a trade to survive so he wouldn’t have to steal for his whole life.” He learned his trade at Boys Ranch and went on to run a crane for 40 years. As for the photograph — and now the statue that was erected in front of the Julian Bivins Museum at Boys Ranch to mirror it — he’s not so embarrassed by it anymore.

“When Cal passed away, the pride of that picture came out,” he said. Then, as his eyes filled with tears and a few moments later he choked through the emotion, “I walked with the greatest man in the world. He took trash and made men, but he never classified us as trash. He gave us a reason to live.”